Computer science education is a global challenge

For the last two years, I’ve been one of the advisors to the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution, a US-based think tank, on their project to survey formal computing education systems across the world. The resulting education policy report, Building skills for life: How to expand and improve computer science education around the world, pulls together the findings of their research. I’ll highlight key lessons policymakers and educators can benefit from, and what elements I think have been missed.

Why a global challenge?

Work on this new Brookings report was motivated by the belief that if our goal is to create an equitable, global society, then we need computer science (CS) in school to be accessible around the world; countries need to educate their citizens about computer science, both to strengthen their economic situation and to tackle inequality between countries. The report states that “global development gaps will only be expected to widen if low-income countries’ investments in these domains falter while high-income countries continue to move ahead” (p. 12).

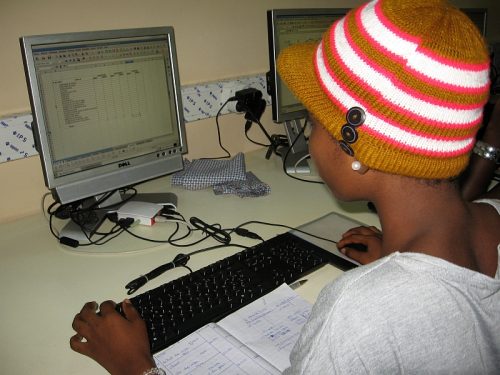

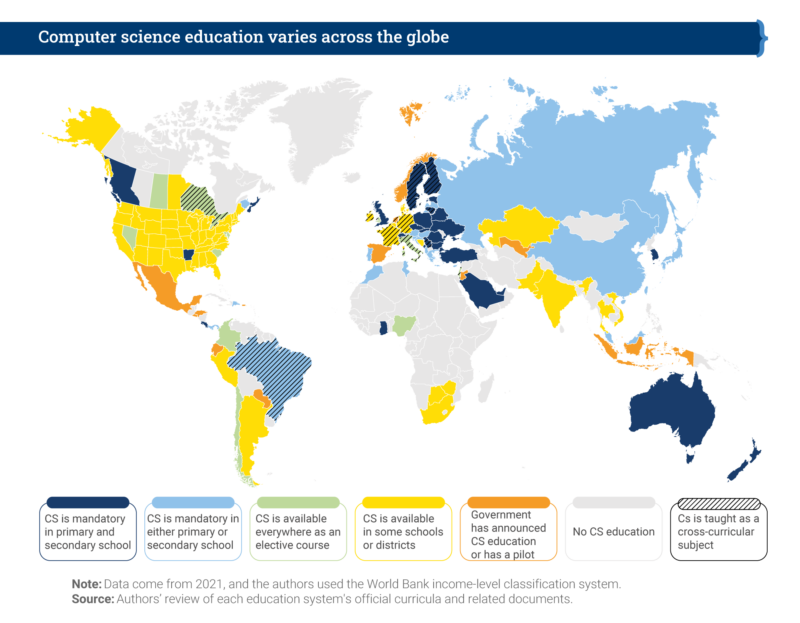

The report makes an important contribution to our understanding of computer science education policy, providing a global overview as well as in-depth case studies of education policies around the world. The case studies look at 11 countries and territories, including England, South Africa, British Columbia, Chile, Uruguay, and Thailand. The map below shows an overview of the Brookings researchers’ findings. It indicates whether computer science is a mandatory or elective subject, whether it is taught in primary or secondary schools, and whether it is taught as a discrete subject or across the curriculum.

It’s a patchy picture, demonstrating both countries’ level of capacity to deliver computer science education and the different approaches countries have taken. Analysis in the Brookings report shows a correlation between a country’s economic position and implementation of computer science in schools: no low-income countries have implemented it at all, while over 20% of high-income countries have mandatory computer science education at both primary and secondary level.

Capacity building: IT infrastructure and beyond

Given these disparities, there is a significant focus in the report on what IT infrastructure countries need in order to deliver computer science education. This infrastructure needs to be preceded by investment (funds to afford it) and policy (a clear statement of intent and an implementation plan). Many countries that the Brookings report describes as having no computer science education may still be struggling to put these in place.

The recently developed CAPE (capacity, access, participation, experience) framework offers another way of assessing disparities in education. To have capacity to make computer science part of formal education, a country needs to put in place the following elements:

- Policy

- IT infrastructure

- Computer science content in the curriculum

- Teacher education

My view is that countries that are at the beginning of this process need to focus on IT infrastructure, but also on the other elements of capacity. The Brookings report touches on these elements of capacity as well. Once these are in place in a country, the focus can shift to the next level: access for learners.

Comparing countries — what policies are in place?

In their report, the Brookings researchers identify seven complementary policy actions that a country can take to facilitate implementation of computer science education:

- Introduction of ICT (information and communications technology) education programmes

- Requirement for CS in primary education

- Requirement for CS in secondary education

- Introduction of in-service CS teacher education programmes

- Introduction of pre-service teacher CS education programmes

- Setup of a specialised centre or institution focused on CS education research and training

- Regular funding allocated to CS education by the legislative branch of government

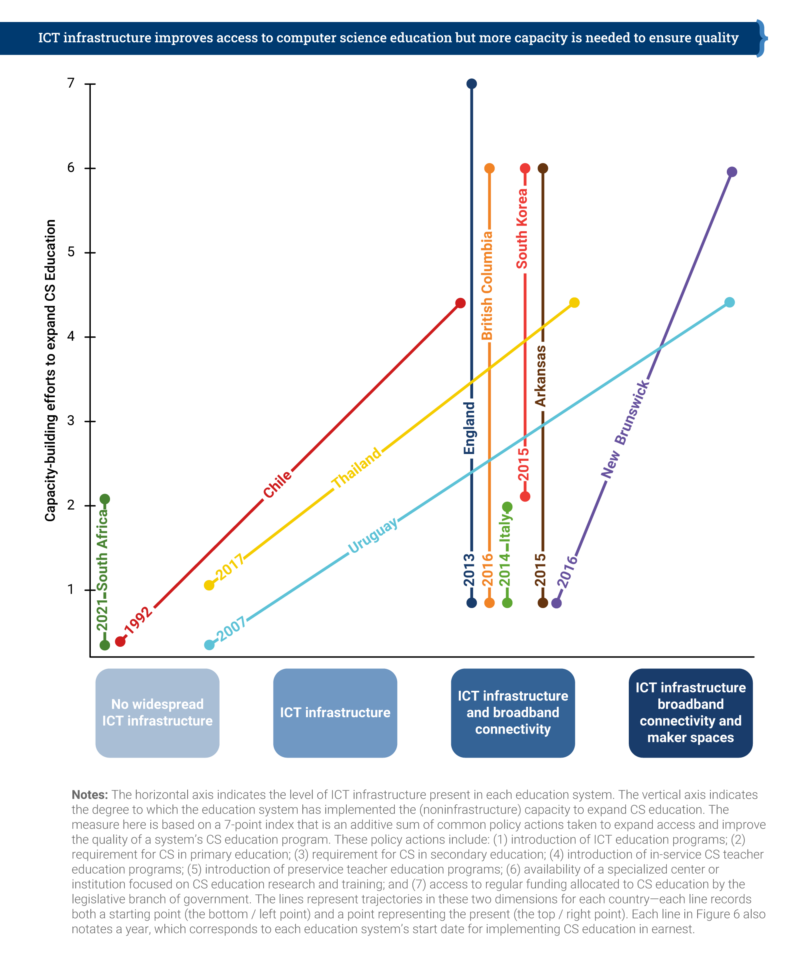

The figure below compares the 11 case-study regions in terms of how many of the seven policy actions have been taken, what IT infrastructure is in place, and when the process of implementing CS education started.

England is the only country that has taken all seven of the identified policy actions, having already had nation-wide IT infrastructure and broadband connectivity in place. Chile, Thailand, and Uruguay have made impressive progress, both on infrastructure development and on policy actions. However, it’s clear that making progress takes many years — Chile started in 1992, and Uruguay in 2007 — and requires a considerable amount of investment and government policy direction.

Computing education policy in England

The first case study that Brookings produced for this report, back in 2019, related to England. Over the last 8 years in England, we have seen the development of computing education in the curriculum as a mandatory subject in primary and secondary schools. Initially, funding for teacher education was limited, but in 2018, the government provided £80 million of funding to us and a consortium of partners to establish the National Centre for Computing Education (NCCE). Thus, in-service teacher education in computing has been given more priority in England than probably anywhere else in the world.

Alongside teacher education, the funding also covered our development of classroom resources to cover the whole CS curriculum, and of Isaac Computer Science, our online platform for 14- to 18-year-olds learning computer science. We’re also working on a £2m government-funded research project looking at approaches to improving the gender balance in computing in English schools, which is due to report results next year.

The future of education policy in the UK as it relates to AI technologies is the topic of an upcoming panel discussion I’m inviting you to attend.

The Brookings report highlights the way in which the English government worked with non-profit organisations, including us here at the Raspberry Pi Foundation, to deliver on the seven policy actions. Partnerships and engagement with stakeholders appear to be key to effectively implementing computer science education within a country.

Lessons learned, lessons missed

What can we learn from the Brookings report’s helicopter view of 11 case studies? How can we ensure that computer science education is going to be accessible for all children? The Brookings researchers draw our six lessons learned in their report, which I have taken the liberty of rewording and shortening here:

- Create demand

- Make it mandatory

- Train teachers

- Start early

- Work in partnership

- Make it engaging

In the report, the sixth lesson is phrased as, “When taught in an interactive, hands-on way, CS education builds skills for life.” The Brookings researchers conclude that focusing on project-based learning and maker spaces is the way for schools to achieve this, which I don’t find convincing. The problem with project-based learning in maker spaces is one of scale: in my experience, this approach only works well in a non-formal, small-scale setting. The other reason is that maker spaces, while being very engaging, are also very expensive. Therefore, I don’t see them as a practicable aspect of a nationally rolled-out, mandatory, formal curriculum.

When we teach computer science, it is important that we encourage young people to ask questions about ethics, power, privilege, and social justice.

Sue Sentance

We have other ways to make computer science engaging to all learners, using a breadth of pedagogical approaches. In particular, we should focus on cultural relevance, an aspect of education the Brookings report does not centre. Culturally relevant pedagogy is a framework for teaching that emphasises the importance of incorporating and valuing all learners’ knowledge, heritage, and ways of learning, and promotes the development of learners’ critical consciousness of the world. When we teach computer science, it is important that we encourage young people to ask questions about ethics, power, privilege, and social justice.

The Brookings report states that we need to develop and use evidence on how to teach computer science, and I agree with this. But to properly support teachers and learners, we need to offer them a range of approaches to teaching computing, rather than just focusing on one, such as project-based learning, however valuable that approach may be in some settings. Through work we’ve done as part of the NCCE, we have embedded twelve pedagogical principles in the computing curriculum we’ve developed, which is being rolled out to six million learners in England’s schools. In time, through this initiative, we will gain firm evidence on what the most effective approaches are for teaching computer science to all students in primary and secondary schools.

Moving forward together

I believe the Brookings Institution’s report has a huge contribution to make as countries around the world seek to introduce computer science in their classrooms. As we can conclude from the patchiness of the CS education world map, there is still much work to be done. I feel fortunate to be living in a country that has been able and motivated to prioritise computer science education, and I think that partnerships and working across stakeholder groups, particularly with schools and teachers, have played a large part in the progress we have made.

To my mind, the challenge now is to find ways in which countries can work together towards more equity in computer science education around the world. The findings in this report will help us make that happen.

PS We invite you to join us on 16 November for our online panel discussion on what the future of the UK’s education policy needs to look like to enable young people to navigate and shape AI technologies. Our speakers include UK Minister Chris Philp, our CEO Philip Colligan, and two young people currently in education. Tabitha Goldstaub, Chair of the UK government’s AI Council, will be chairing the discussion.

Sign up for your free ticket today and submit your questions to our panel!

5 comments

Harikrishnan N

Team, I’m from India I would like to start raspberrypi foundation classes across India to accelerate computer education. Please advise the procedure.thanks

Raspberry Pi Staff Vasundhara Srivastava

Hi Hari ji,

So glad to see your excitement to start activities in India. My name is Vasu and I manage Raspberry Pi Foundation activities here in India, and I would love to chat with you. How about you drop me a line at vasu@raspberrypi.org and we can take this forward?

Meanwhile you can check out some of our Code activities and CoderDojo activities here in India.

Code Club – https://youtu.be/26UzVJIDW8I

CoderDojo –

https://youtu.be/UsD3SblMZVQ

Chat soon!

Joachim Quainoo

Hello,

I currently stay in France but I come from Ghana. I would wish to start Raspberry Foundation in Ghana. We can collaborate in the name of my NGO, MyEducation MyStory and push for the digital studies of Ghanaian pupils in remote areas.

I look forward to an exchange with you with regards to this initiative.

Cordially

Joachim Quainoo

joachim.quainoo@gmail.com myeducationmystory@gmail.com

Raspberry Pi Staff Sonja

Hi Joachim,

That’s brilliant!

I work with partners around the globe that want to advance this educational work. I’ll drop you and email to start a conversation.

D Laloux

Hi Joachim,

With the help of a small Togolese team, I have worked at promoting the use of the Raspberry Pi in rural schools in Togo since 2014. We install small labs with 21+ workstations, often in unused classrooms. We started with the RPi 1, and we moved on to the RPi 2, RPi 3, and now the RP 4… We still run RPi 3s in most of our labs. We currently have 5 labs installed in villages where one would never expect such resources to be available for local schools. We are planning a 6th lab for 2022.

All labs are built on the same “model” : from power circuits and LAN to the furniture, even the color scheme and the posters ;-). All labs use a similar Ubuntu image, installed with all of the software that one could expect to find in a secondary school.

In all partner schools, the most difficult hurdle is to engage teachers in the project.

My dream is now to attract the attention of other Organisations, Institutions, NGO… who plan to offer ICT equipment to similar schools, and to convince them to consider our “model” as a much better alternative to “old retired equipment” or recent, sophisticated, equipments (such as laptops) which are often too fragile for such (tropical) environments.

Maybe you want to have a look at our website (www.initic.africa).

Of course we would be very happy to share our experience.

Kind regards,

dl